Treatment-seeking behaviour is defined as sequence of actions that taken by individual in responding to their illness. Many people, including forest workers differ in their willingness to seek health assistance. Some are immediately ready for early diagnosis and expect proper treatment. Others probably only when in a great pain or in advance state of their illness. Following qualitative analysis, this section presents the characteristics of the informants, occupational groups among forest workers, and themes of analysis, such as malaria beliefs and risk behaviour, treatment-seeking behaviours, methods to access forest workers and future participation.

Description of participants

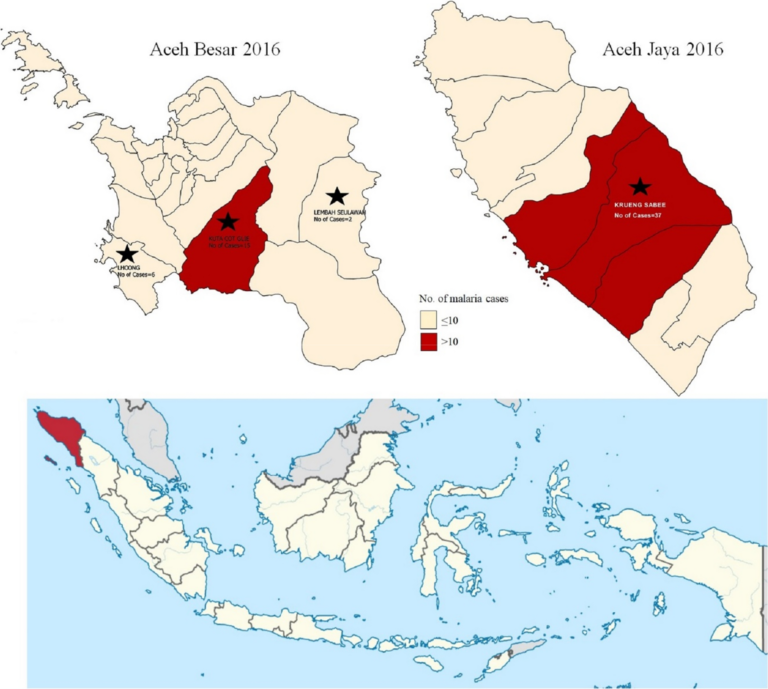

The study included 231 participants, with approximately equal numbers across the four subdistricts (Table 1). Median age of male forest workers was 30 years (range 18 to 56), whilst median age of other KIs was 36 years (range 19 to 73) with a male to female ratio of 1.8 to 1. Forty-one individuals (34 males and 7 females) contacted declined to participate due to work activities in the forest (17), immediate family matters (11), uncontactable (8), and unwell (5) on the assigned day of group discussions.

Occupational groups

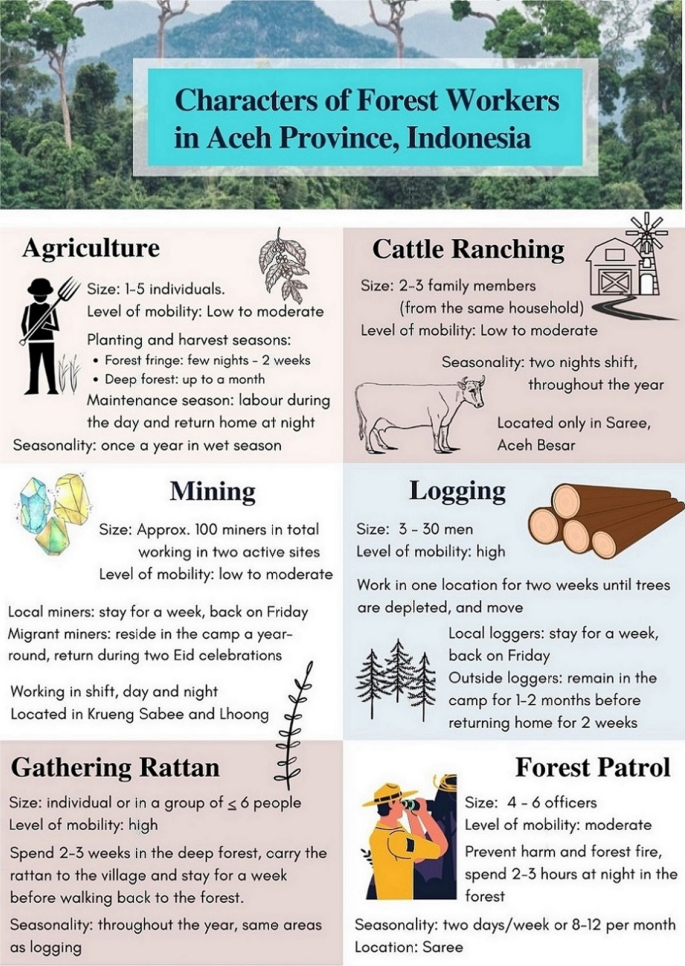

KIs described six main activities that occur in forested areas: agriculture; cattle ranching; logging; mining; gathering rattan; and forest patrol (Fig. 2). Agriculture was reported in all sub-districts and was small scale, with work groups of 1 to 5 individuals (4 to 5 during planting and harvesting seasons) typically from the same village. Crops cultivated in forest fringe areas included corn, rice, chili, candlenut, cassava and areca nuts, clove, nutmeg, sweet potato, yam, peanut, and eggplant, while durian, cacao, banana, and coffee are generally grown deeper in the forest. Agricultural forest workers typically labour during the day and return home to their villages at night, except during the work-intensive planting and harvest seasons, when overnight stays at plantations become more common. Farmers who are unable to return home each evening reported spending from a few nights to 2 weeks at forest fringe plantations and up to 1 month at plantations located deeper in the forest, in part to work and in part to guard their crops from animals. During these periods, farmers sleep in simple huts.

Figure 3 illustrates that cattle ranches in forested areas were only reported in Saree; they are located in the forest fringe and collectively owned by villages. Residents take turns spending the night (in 2-night shifts) at the ranches to guard cattle, generally in groups of 2 to 3 family members from the same household.

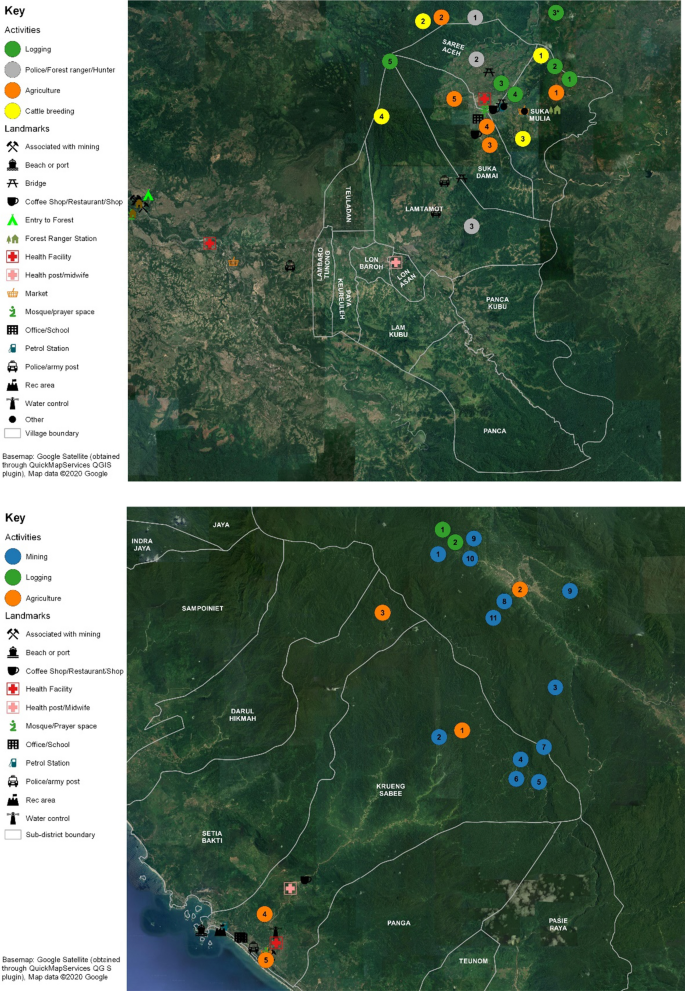

Activity maps reported by the forest workers in Saree and Krueng Sabee. Illustrates activities in agriculture (orange), logging (green), mining (blue), cattle breeding (yellow) and police/forest ranger/hunter (grey). Base map source: Google Satellite, obtained through Quick Map Services QGIS plugin. Map data @2020 Google. Access date: January 9, 2020

Logging was reported by KIs in Kuta Cot Glie and Saree, at forest work sites that typically comprise from 3 to 30 men and shift location frequently; loggers were described as staying at a given site for about 2 weeks until trees are depleted before moving elsewhere. Because forest work camps are generally located from 2 to 6 h by vehicle from the nearest village, followed by 30 min on foot to the logging work site, loggers who reside within Aceh typically sleep at the logging camp for a week at a time, returning home on Fridays to pray and purchase the logistics and food for the group. Loggers who reside outside of Aceh (typically North Sumatra or West Java) often remain at the logging camp for 1 to 2 months before returning home for about 2 weeks.

Gathering rattan (harvested from wild climbing palms belongings to sub-family Calamoideae are used for baskets and furniture) was also described as a frequent activity in Kuta Cot Glie and Krueng Sabee; this activity occurs throughout the year in the same areas as logging. Workers frequently work alone or in a group of up to six people, and the gatherers spend 2–3 weeks in the deep forest, then carry the rattan to the village and typically stay a week before returning to the forest.

Participants described two mines in the forests of Krueng Sabee and Lhoong, which employed approximately 100 labourers in total. The Krueng Sabee mine is located two hours by vehicle from the nearest village. Miners included both local (from within the district), and migrant workers (travelling from elsewhere in Aceh Province, West Sumatra and several provinces in Java). The local miners usually stay at the mining camps during the week and return home on Fridays, whereas migrant miners generally reside at the camps year-round, returning home only during the two annual Eid celebrations (Eid al-Fitr at the end of Ramadan and Eid al-Adha approximately 2 months later). Miners reported sleeping near their mining site.

The Lhoong mine is located 20 min from the nearest village on the forest fringe and is owned by a foreign company that has ceased operations; however, about 20 residents of local communities often enter and mine there illegally during the evenings, returning home each day to process material at a plant located in the village.

One KI was a police officer who trained newly recruited cadets in the police academy in Saree. Over a period of 2 to 4 months, he conducted annual intensive training for around 300 cadets which required him to march on foot and spend nights in either military tents or on the ground under the open sky along with 50 trainees. Apart from regular training activities, police officers perform routine and 24-h patrol shifts at the base.

The main tasks of forest rangers include patrolling in forested areas to prevent harm and forest fire, and raising awareness to prevent illegal logging. In a group of 4–6 officers, they routinely patrol their remote posts –located around six kilometres from the outermost village– for 2–3 h at night. Forest rangers in Saree generally work two days per week or 8–12 days per month from 9 a.m to 5 p.m.

Malaria beliefs and risk behaviours

Across study sites, most participants perceived forest workers to be at high risk for malaria. Some participants believed that malaria risk was limited to people who work and stay overnight in the forest or mountains, and stated that individuals living in villages were rarely infected. Many participants reported that spending time in cold places and sleeping out in the open air or in a simple hut without using mosquito net were the main reasons people contract malaria. The majority of participants perceived malaria patients to be predominantly men, with a much smaller percentage of children:

As far as I know there are several villagers here who got malaria according to blood test results. Most of them are farmers who work in the fields, most are male, but some are children… but most are male because they often have to sleep out in the open air in the field, they don’t use mosquito net (Participant SR004, male, 39, community leader).

At all study sites, forest workers described the presence of monkeys, which they reported witnessing during daytime travel within the forest. Most reported seeing long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis, Local name: Bukreh), southern pig-tailed monkeys (Macaca nemestrina, Local name: Siben or Beruk) and Sumatran surili (Presbytis melalophos, Local name: Buduk or Budeng). Several participants reported that monkeys often come to the logging sites or to forest plantations at night to eat crops during harvest season. Most participants declared there was no interaction between the workers and the monkeys, while a small number of workers reported feeding them fruit, capturing them for sale, bringing them home as pets or chasing them away.

Almost all participants described malaria symptoms (N = 279) as one or more of the following: headache (39), chills (33), fever (31), muscle and joint pain (30), feeling hot and cold or sijuk suum (29), weak (21), vomiting (11), nausea (8), and dizziness (7).

Most participants reported low rates of prevention practices among forest workers, while several reported the use of bed nets, mosquito coils, repellent and medication to prevent malaria symptoms. The most common behavioural risks perceived were not using mosquito nets or repellent at night, working and sleeping outdoors at night, and doing no more to ward off mosquitoes when sleeping than lighting a fire.

I don’t think we would feel anything if a mosquito bit us… If we remember, we apply [repellent]. Sometimes if we get too tired after marching from morning until afternoon, we fall asleep fast. (Participant SR016, male, 30, police officer).

Many participants believed that eating certain foods protects against malaria, such as papaya leaves, bitter melon [local name: paria or pare], mahogany seeds, cats’ whiskers, and lanzone root [local name: langsat]. Others mentioned traditional herbs or jamu, made from leaves of king of bitter [local name: bratawali] and long jack leaves [local name: pasak bumi or tongkat Ali]. Wearing charmed stones was seen as protecting against mosquito bites.

Many participants said they did not regularly use bed nets because they made breathing difficult or were hot and uncomfortable. Some believed that chemicals used to treat the nets resulted in odours that irritate the eyes and skin. A number of participants who were willing to utilize the mosquito nets in their working areas lamented that they were expensive, often out of stock, or were not distributed specifically to forest workers. Some forest workers viewed prevention as unnecessary because they can buy medication whenever they feel ill.

Treatment-seeking behaviours

Forest workers described a variety of strategies for fighting off malaria symptoms when they experienced them in order to continue working. Many reported that they tended to ignore symptoms or self-treat with medications they brought from local pharmacies as a precaution when travelling into the forest, including analgesics, antipyretics, food supplements and anti-malarial drugs.

When malaria symptoms persisted after self-treatment, the workers described visiting a pharmacy as soon as they arrived in the village and purchasing the commercial brand of chloroquine without being tested for malaria.

Bayer. Sometimes we bought Paramex [an analgesic], but when we arrived to the mountain we didn’t need that because we were sick from something else. No, they [people at the pharmacy] don’t check for it [malaria]. We ask them to give us some medicines as a precaution (Participant KG101, FG, patients and their co-workers).

While some KIs reported that malaria patients seek care at PHC’s, participants more often described presenting to the nearest private clinic, often run by a nurse or midwife. Although private clinics rarely have laboratory facilities available, they were seen as more convenient because they were open in the evening after work, conducted examinations quickly and were run by well-known people. Private clinics were also perceived to be effective at treating patients.

They [the private clinic] will check the patient’s health condition and then give an injection. The sick usually gets better in one night. (Participant KS008, male, 40, toke).

Other participants reported that forest workers often consulted traditional healers before going to the PHC, particularly when they or their family believed that malaria was by an evil spell or by a bad spirit encountered at a work site. Some participants saw traditional healers as both affordable and effected, and trusted in their treatments to effectively repel the disease, which included written prayers, figure or images with religious or mystical properties [local: jampi-jampi or rajah]. Two participants, a community member and toke, stated that some private clinic staff also refer patients to traditional healers.

It’s what we believe… It’s our tradition, to first find out whether the sick person is possessed by an evil power or not. That’s why we bring the patient to a traditional healer, to get rid of the evil power… and the patient doesn’t have to pay much either (Participant KG105, FG, forest fringe community).

One of the primary barriers for seeking medical treatment among forest workers was the high cost of transportation to health facilities from forest work sites or their homes. One KI stated,

One of the reasons I didn’t go to primary health centre perhaps because it’s too far from my house. Not all people here have a car. So first aid is by taking traditional herbs (Participant LH101, FG, patients and their co-workers).

In addition, some participants perceived PHC’s to have inconvenient operating hours as well as unhelpful, disrespectful or untrustworthy staff.

When people go to PHC, sometimes staff are ignorant. They receive many complaints from the villagers. Perhaps people who go to PHC are lower middle class and PHC staff are disrespectful. There are two to three people there [at the PHC] who seem unmotivated to provide the services. We are not too happy. There a case… it happened 2 months ago… one of the doctors gave a wrong diagnosis (Participant SR004, male, 39, community leader).

Furthermore, stock outs were cited as a barrier for seeking care at PHC’s: one KI (a police officer) reported stock outs of anti-malarial medications at a police academy clinic.

We are out of [anti-malarial] medicines right now… I think I saw some quinine pills available there…I don’t know what that is, but we rarely use them (Participant SR016, male, 30, police officer).

Among migrant workers, seeking treatment at PHC’s was reported to be more complicated because they were not registered in the local health insurance scheme. As a result, several participants reported that migrant workers tend to prefer private clinics in cases of emergency. One toke who employed migrant workers explained why he chose to take his employees to private clinics instead of to the PHCs:

Sometimes we employ workers from outside this village, and I cannot take care of everything because the procedure is too long. They [staff at the PHC] ask for family card identification, this and that. It’s a long procedure. We need a quick medical treatment because we bring a sick person here (Participant KS018, male, 40, toke).

A number of participants informed that forest workers avoided seeking treatment at PHCs due to a fear of needles and misconception about injected treatment for malaria. Others reported that they preferred to first seek help from traditional healers, particularly if their symptoms are mild.

Before going to Puskesmas, we usually see a traditional healer [Local: dukun]. That’s because we don’t know what we have… Why we are sick. People say if we fell into a trance, we cannot be injected…. It’s being possessed by an evil spirit… touched by a ghost (Participant LH102, FG, patients and their co-workers).

Several community leaders, tokes and forest workers viewed PHCs and hospitals as preferable when illness was severe or potentially fatal, or when symptoms worsened following initial treatment elsewhere, especially because services at the government health centres are free of charge. Once at a PHC, participants recounted receiving laboratory confirmation of malaria prior to receiving treatment.

Participants were generally unwilling to speak about illegal forest workers. However, some speculated that they do visit the PHC and sometimes have misconception about malaria treatment.

Methods to access forest workers

Determination of whether VB and/or PR-based surveillance were likely to be feasible methods to access forest workers was based on themes that emerged from the data (Table 2). VB was considered a practical option for occupational groups that tend to stay overnight or work at well-defined work sites during mosquito biting hours that are geographically accessible, safe to visit and accessible, such as miners. PR was considered for groups whose members tend to interact with one another frequently and are likely to be willing and able to present to a surveillance officer located in a village or settlement within 2 to 3 weeks of referral.

Agricultural workers, rattan gatherers and rangers were seen as accessible by PR because they often hail from the same village and know one another, whereas efforts to recruit at work sites may confront several challenges: individuals tend to work alone or in small groups that do not work daily or during predictable schedules, and are not organized by tokes; those who return home in the evenings would generally be unavailable working during the day and travel to more remote work sites would be infeasible during the rainy malaria season.

The area is difficult to reach and also very far. There’s a chance too that the people you’re going to see are not available that time. It is difficult also to communicate with them because there is lack of communication device… Besides that, it’s very difficult to reach the place (Participant SR102, FG, forest fringe community).

Because cattle ranchers operate collectively in a well-organized group, PR or a screening event held in the community coordinated by tokes, village leaders or local midwives were seen as promising options, while participants did not view VB as an ideal plan for conducting a study.

It’s not a suitable place to meet at work place, it’s better to meet here [in the village], so it can be explained to them…what malaria drug is, how we can prevent malaria. We can arrange the meeting in Meunasah [local: small mosque] … or…in the village hall (Participant SR005, male, 53, cattle toke).

In contrast, PR was not seen as possible for gold miners in Krueng Sabee, because local and migrant subgroups often do not interact with each other. However, VB was reported to be a feasible and acceptable option, as miners are likely to be accessible at the work site: they reside there during extended periods, and therefore could be accessed when off shift. In addition, the tokes interviewed at the mines expressed willingness to facilitate access for screening purposes.

Furthermore, mining camps are reachable within two hours from the district centre, which would facilitate the transportation of equipment and supplies required for a VB intervention. Tokes suggested the importance of gaining support of village leaders when planning VB screening. Of note, females are forbidden at the mining camps because they are thought to harbor bad luck, which would preclude female nurses and other staff from participating in VB surveillance.

A routine malaria examination every 3 months was viewed as beneficial for forest workers and their employers; tokes also strongly requested feedback on the malaria test results.

When you come to check their health condition, the workers would know about their health condition…. If during the medical check there are symptoms of sickness, they will know it too. But we have never had our health condition checked, there’s no explanation about health issues before (Participant KS018, male, 40, toke).

However, loggers in Lhoong and Kuta Cot Glie were seen by most participants as unreachable at their work sites, which tend to be remote and difficult to access. In addition, some participants reported that the presence of VB surveillance staff in the forest would be viewed as suspicious by loggers.

“It’s not possible to ride a motorcycle passing that road. They would think negative things… [such as] why do these people come here, are they logs buyer? It would raise questions (Participant LH105, FG, forest community).

Finally, participants reported that loggers would not want to be distracted from their work, and therefore would not be interested in participating in VB surveillance. The majority of participants also viewed PR as an infeasible strategy for reaching loggers. Participants reported that local and migrant loggers tend to not interact with each other, and most migrant workers do not stay in local communities upon leaving the work site. Tokes were supportive of PR, however, and offered to assist with surveillance by making workers available and inviting them to meet at a workshop facility in the local village or at the toke’s residence. Because tokes change frequently and one participant felt community leaders should also be involved in helping to plan for PR surveillance.

The toke will contact the workers, because we don’t know the workers ourselves…they are not from here…all of them are outsiders (Participant KG105, FG, forest community).

In Saree, where the majority of the forest is protected, KIs reported that most logging that occurs is illegal. Because of this, loggers and tokes in Saree would not be amenable to work site screening. KIs reported that illegal loggers would be open to participating via PR, but they would probably not admit to engaging in logging and would instead say they were doing other activities in the forest. For police cadets and forest rangers, however, venue-based screening is more likely feasible compared to the other.

Future participation

Most informants expressed interest in participating in future malaria surveillance activities, provided they do not interfere their work. All occupational groups preferred cash incentives, with desired minimum amounts varying from USD 3.85 to 7.69, in addition to compensation for any transportation cost to travel to the study location.