An Indonesian government plan to build a vast agricultural estate to shore up food security threatens Indigenous territory and risks destroying millions of hectares of climate-critical tropical rainforests, environmental activists have warned as the Southeast Asian nation hosts the G20 Summit in Bali.

The Jokowi government’s food estate programme was announced in 2020 in response to food security concerns triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic. The programme is now in its third year, and President Joko Widowo had in October urged ministers to scale it up, despite techinical problems and reports that crop yields have fallen.

The project aims to increase food production in Indonesia by three per cent a year, and boost the country’s rice reserves. The food estate programme is the rebirth of a huge rice cultivation project Indonesia launched in the 1990s known as the mega rice project (MRP), which failed because farmers could not grow rice on nutrient-poor peatland soil.

Environmental campaign groups including Greenpeace, which announced it would not be attending the G20 Summit on Saturday because its campaigners had been blocked by the authorities on their journey on bicycles to Bali, unfurled a banner on a patch of deforested land in Gunung Mas, Central Kalimantan to protest against the project.

The government plans to develop 164,600 hectares of land for food estates in Central Kalimantan, an area of peatland soil where the MRP was located. It also has plans for large agricultural plantations in North Sumatra and South Sumatra in the country’s west, and East Nusa Tenggara and Papua in the east, and has earmarked IDR2.3 trillion (US$150 million) for the project.

In Gunung Mas, a district in Central Kalimantan, 31,719 ha of cassava plantations are planned as part of the food estate programme. To date, 760 hectares of forest has been chopped to make way for cassava without consent from the Indigenous Dayak community which lives in the area, and has resulted in the release of 77,000 tonnes of carbon, according to the Feeding the Climate Crisis report.

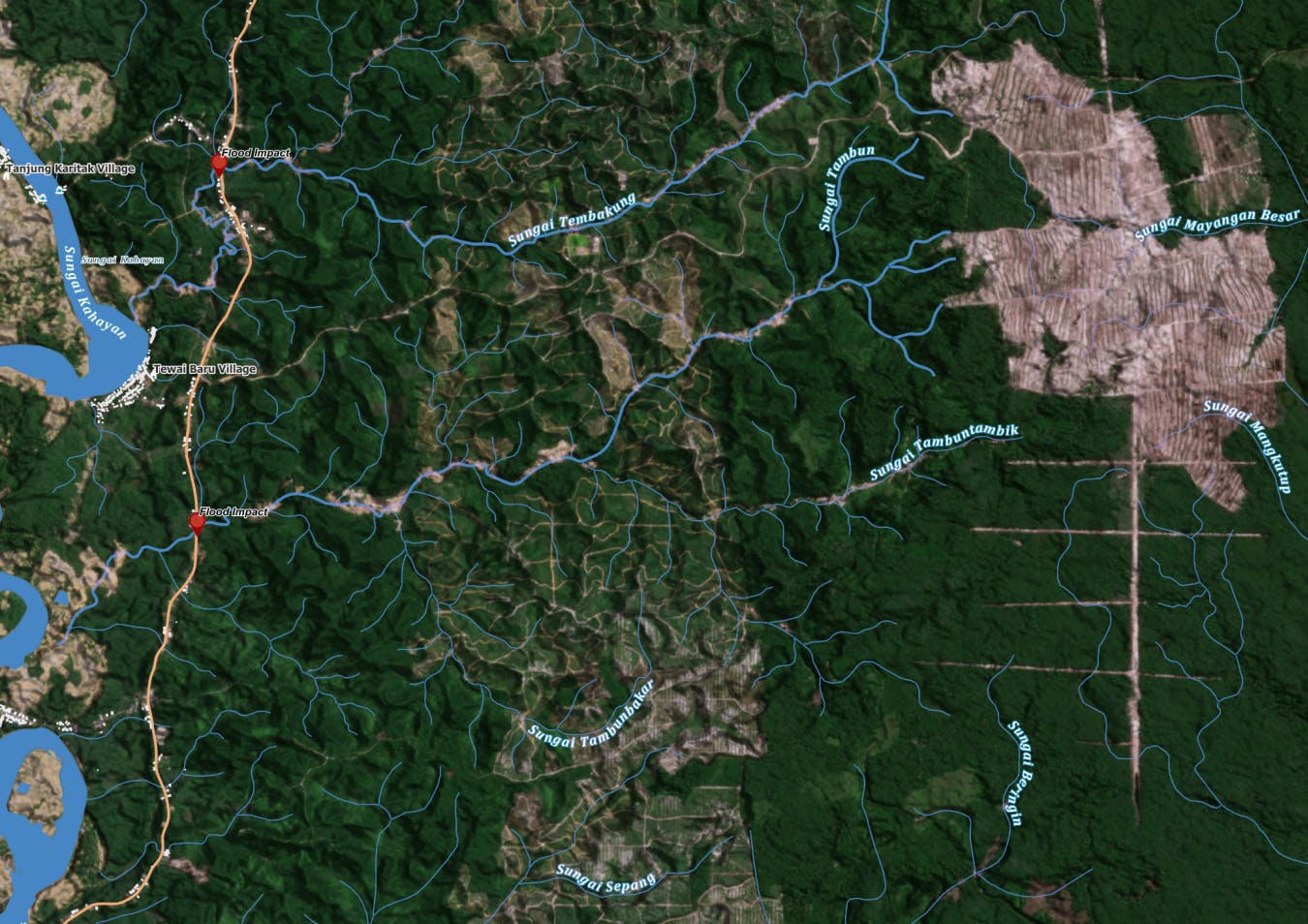

A patch of forest cleared by the Ministry of Defence drains into the Tambun and Tambakung rivers. Flooding is now more severe in the areas marked in red. Image: Greenpeace illustration based on Planet Imagery dated July 2022.

A patch of forest cleared by the Ministry of Defence drains into the Tambun and Tambakung rivers. Flooding is now more severe in the areas marked in red. Image: Greenpeace illustration based on Planet Imagery dated July 2022.The report, which was assembled by green groups Greenpeace Indonesia, WALHI, LBH Palangkaraya and Save Our Borneo, revealed that irrigation canals dug in Gunung Mas have resulted in flooding in neighbouring areas, and have left the area prone to fires in the dry season, when the drained peat dries out.

“This approach is not only failing to produce the promised cassava, but it will never produce a diverse, nutritious and culturally appropriate diet,” commented Syahrul Fitra, senior forest campaigner for Greenpeace Indonesia. “There are better ways – with ecological farming and traditional agroforestry we can feed the world and cool the planet,” he said.

The NGOs launched the report as world leaders negotiate how to reduce climate-wrecking carbon emissions at the COP27 talks in Egypt, and as Indonesia hosts the G20, a meeting of the world’s 20 largest economies, this year in Bali.

Yeb Saño, Greenpeace’s COP27 head of delegation, said: “Our industrial approach to agriculture is the biggest cause of biodiversity loss and responsible for a third of climate-wrecking GHG emissions. It is also self-defeating: the 2022 UN Food Security report tells us global food insecurity is being driven by climate extremes. So, we face not only a food crisis, but an existential crisis arising from our failure to protect nature. We know the two are inextricably linked. We cannot solve one without dealing with the other.”