Cyber security researchers have shed light on the Linux variant of a relatively new strain of ransomware called Helldown, suggesting that threat actors are broadening the focus of their attack.

“Helldown deploys Windows ransomware derived from LockBit 3.0 code” – Sekoia said in a report shared with The Hacker News. “Given the recent development of ransomware targeting ESX, it appears that the group may be evolving its current operations to target virtualized infrastructures via VMware.”

Helldown was publicly documented for the first time Halcyon in mid-August 2024. describing it’s like an “aggressive ransomware group” that infiltrates target networks by exploiting security vulnerabilities. Some of the prominent sectors targeted by the cybercriminal group include IT services, telecommunications, manufacturing and healthcare.

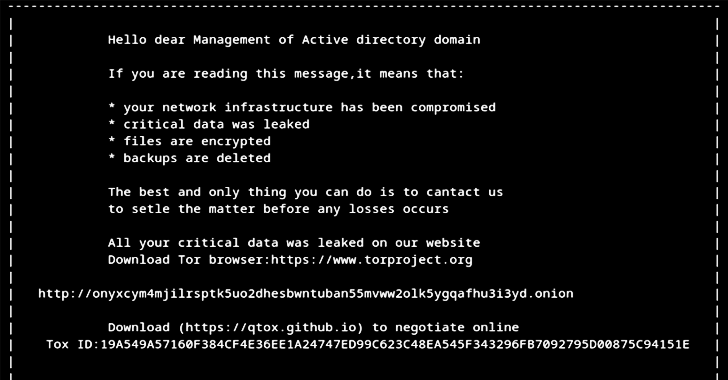

Like other ransomware teams, Helldown is there of course for using data-leaking sites to pressure victims into paying a ransom by threatening to publish the stolen data – a tactic known as double extortion. It is believed to have attacked at least 31 companies over a three-month period.

Truesec, in an analysis published earlier this month, detailed Helldown attack chains that were seen using Zyxel’s Internet-facing firewalls to gain initial access, followed by retention, credential harvesting, network enumeration, defense evasion, and lateral movements to final deployment of the ransomware.

Sekoia’s new analysis reveals that attackers are exploiting known and unknown security flaws in Zyxel devices to breach networks, using a backbone to steal credentials and create SSL VPN tunnels with temporary users.

The Windows version of Helldown, once launched, performs a series of steps to exfiltrate and encrypt files, including removing shadow copies of the system and terminating various processes related to databases and Microsoft Office. In the final step, the ransomware binary is deleted to cover its tracks, the ransom note is reset, and the machine is shut down.

Its Linux counterpart lacks obfuscation and anti-debugging mechanisms, while including a short set of functions for searching and encrypting files, but not before enumerating and killing all active virtual machines (VMs), according to a French cybersecurity company.

“Static and dynamic analysis revealed no communication in the network, and no public key or shared secret,” the report said. “This is notable because it raises questions about how an attacker would be able to deliver a decryption tool.”

“Terminating the virtual machines before encryption gives the ransomware write access to the image files. However, both static and dynamic analysis show that although this function exists in the code, it is not actually called. All these observations suggest that the ransomware is not very sophisticated and may still be under development.”

Windows Helldown artifacts were found to be similar to the behavior of DarkRace, which appeared in May 2023 using LockBit 3.0 code and was later renamed DoNex. A decryptor for DoNex was made available by Avast back in July 2024.

“Both codes are variants of LockBit 3.0,” Sekoya said. “Given Darkrace and Donex’s history of rebranding and their significant similarities to Helldown, the possibility of Helldown being another rebrand cannot be ruled out. However, at this stage, this connection cannot be definitively confirmed.”

The development comes after Cisco Talos disclosed another new ransomware family, known as Interlock, that targeted the healthcare, technology and government industries in the US, as well as manufacturing organizations in Europe. It is capable of encrypting both Windows and Linux machines.

Ransomware-distributing attack chains have been observed using a spoofed Google Chrome browser updater binary hosted on a legitimate but compromised news website that, when launched, launches a Remote Access Trojan (RAT) that allows attackers to extract sensitive data and run PowerShell commands designed to dump payloads to collect credentials and perform reconnaissance.

“In its blog, Interlock claims to target organizations’ infrastructure using unpatched vulnerabilities, and claims its actions are motivated in part by a desire to hold companies accountable for poor cybersecurity, in addition to monetary gain,” Talos researchers. said.

Interlock is believed to be a new group that emerged from Rhysida’s operators or developers, the company added, citing similarities in the ransomware’s trades, tools and behavior.

“Interlock’s potential association with Rhysida operators or developers would be consistent with several broader trends in the cyber threat landscape,” it said. “We’ve seen ransomware groups diversify their capabilities to support more advanced and diverse operations, and ransomware groups are becoming less isolated as we see operators increasingly working together with multiple ransomware groups.”

Coinciding with the arrival of Helldown and Interlock is another new entrant to the ransomware ecosystem called SafePay, which is said to have targeted 22 companies to date. SafePay, on Huntress, also uses LockBit 3.0 as its foundation, suggesting that LockBit source code leak gave birth to several options.

In two incidents investigated by the company, “the threat actor’s activity was determined to originate from a VPN gateway or portal, as all observed IP addresses assigned to the threat actor’s workstations were in the internal range,” Huntress researchers said. said.

“The threat actor was able to use valid credentials to access client endpoints, and no RDP was enabled, no new user accounts were created, or any other security was created.”