- Unlawful killings, buildup of security forces in vicinity of a planned gold mine concession

- Authorities restrict daily life of Indigenous Papuans, including hairstyle

- Lack of consultation with communities affected by gold mine plans

Indonesian authorities should immediately halt plans to develop a sprawling gold mine the size of the city of Jakarta in volatile Papua Province, where it risks fueling conflict and violating the land rights of Indigenous Papuans, Amnesty International said in a new briefing published today.

Intan Jaya Regency, where the gold ore deposit known as Wabu Block is located, has become a hotspot of conflict between Indonesian security forces and Papuan independence groups in recent years.

In the briefing, Amnesty International documents how there has been an alarming build-up of security forces in the area since 2019, with 12 suspected cases of unlawful killings carried out by security forces, and Indigenous Papuans subjected to increasing restrictions on freedom of movement as well as routine beatings and arrests.

Residents of Intan Jaya told Amnesty International that they use the proposed mining area for cultivating crops, hunting animals and collecting timber.

“By disregarding the needs, desires and traditions of Indigenous Papuans, the planned development of Wabu Block risks aggravating a rapidly deteriorating human rights situation,” said Usman Hamid, Executive Director of Amnesty International Indonesia. “People in Intan Jaya are living under an increasingly harsh and violent security apparatus that exerts control over many aspects of their daily lives, and now their livelihoods are under threat from this ill-conceived project. Simply put, Wabu Block could be a recipe for disaster.”

By disregarding the needs, desires and traditions of Indigenous Papuans, the planned development of Wabu Block risks aggravating a rapidly deteriorating human rights situation.

Usman Hamid, Executive Director of Amnesty International Indonesia

From March 2021 to January 2022, Amnesty International carried out remote interviews with 31 people about the situation in Intan Jaya Regency, including Indigenous Papuans, local authorities, human rights defenders and representatives of civil society and religious organizations. They described how armed clashes and human rights violations have risen dramatically over the last two years.

Threats to way of life

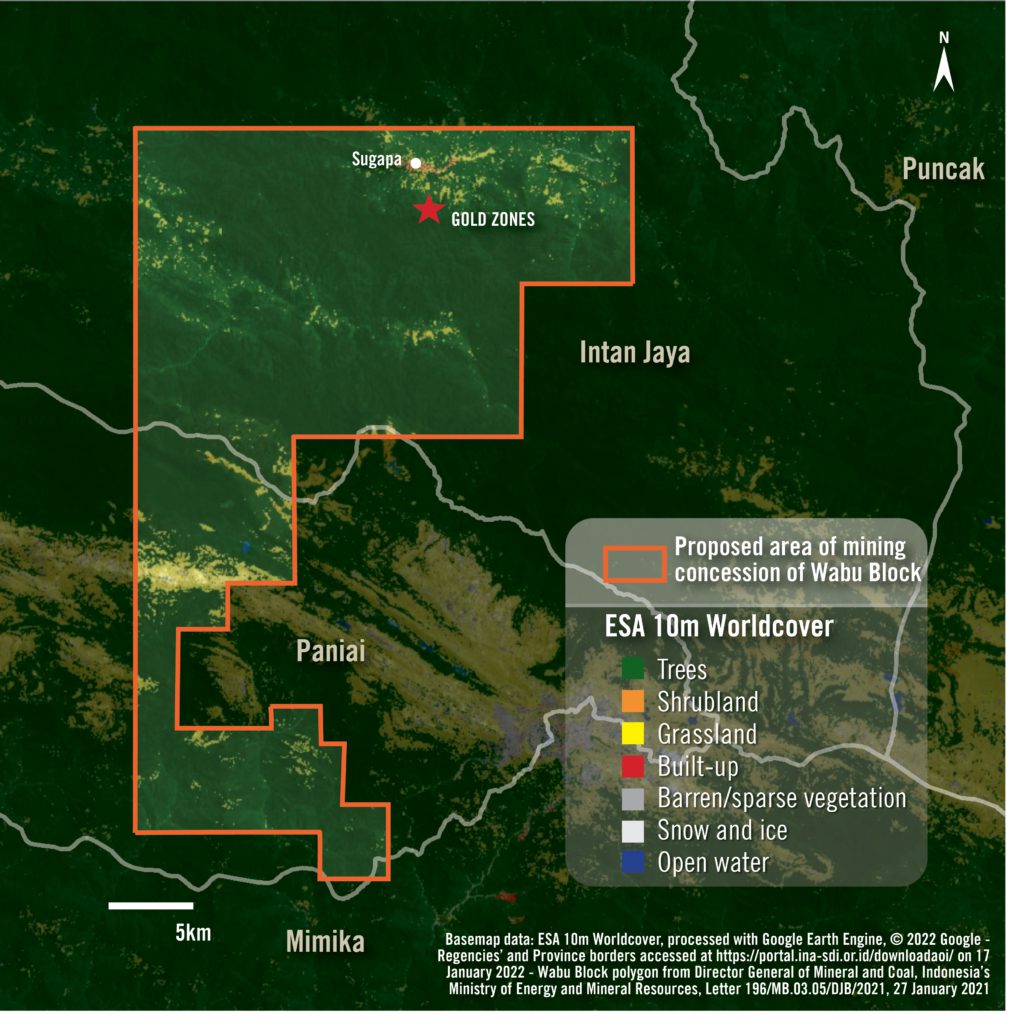

Since at least February 2020, there have been official plans to develop mining activities in Wabu Block. Located south of Sugapa district, the capital of Intan Jaya Regency, Wabu Block holds approximately 8.1 million ounces of gold, making it one of Indonesia’s five largest known gold reserves.

Wabu Block is currently under the licensing process of the Indonesian Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. According to official documents obtained by Amnesty International, the proposed mining area covers 69,118 hectares – about the size of Indonesia’s capital city Jakarta.

Indigenous Papuans said they fear loss of lands and livelihood as well as environmental pollution.

“If there is mining, we will have no land for gardening; livestock will not get fresh fruit directly from the forest, and even our grandchildren will lose customary land,” Lian, a local Indigenous man, told Amnesty International.

In September 2020, a senior Indonesian official expressed his intention to let state-owned mining company PT Aneka Tambang Tbk, also known as ANTAM, develop mining activities in Wabu Block. In letters sent to ANTAM and to the Indonesian Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources in February 2022, Amnesty International laid out human rights concerns about the project and posed several questions. At the time of publication, neither the government nor the company has responded.

While Amnesty International has not found any evidence that either ANTAM or the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources are directly involved in the conflict in Intan Jaya, it is concerned about the potential human rights and environmental impacts of mining in Wabu Block in the context of the existing conflict.

“The government has an obligation to obtain the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous Papuans likely to be affected by the mine. But in a climate of violence and intimidation, it is hard to imagine how such a consultation process could meet international standards,” said Usman Hamid. “The first step is to ascertain whether a full and effective consultation is even feasible under the existing circumstances. In the meantime, Indonesia should press pause on Wabu Block.”

Burned bodies

Conflict between Papuan pro-independence groups and Indonesian security forces has existed for decades. But Intan Jaya Regency emerged as a new hotspot in Papua after October 2019, when members of an armed pro-independence group killed three motorcycle taxi drivers, whom they accused of being spies.

As part of the new research, Amnesty International has identified 17 posts occupied by security forces in Sugapa district, capital of Intan Jaya. According to interviews, only two out of the 17 posts existed before October 2019. The growth of the security force presence has been accompanied by an increase in unlawful killings, raids and beatings.

The briefing documents 12 suspected unlawful killings carried out by members of Indonesian security forces in Intan Jaya in 2020 and 2021.

These account for over a quarter of the total number of suspected unlawful killings carried out by security officers across 42 regencies and cities in Papua and West Papua provinces documented by Amnesty International in the same period.

The cases include two brothers, Apianus and Luter Zanambani, whose bodies were burned by security forces after they were detained during an April 2020 raid in Sugapa district.

Cases of unlawful killings by security forces are common in Papua but accountability is rare, as documented by Amnesty International in the 2018 report ‘Don’t bother, just let him die’.

Indigenous Papuans also described to Amnesty International incidents in which members of security forces had beaten residents of Intan Jaya.

“Indonesian authorities have long failed to adequately investigate suspected cases of unlawful killings and other reports of human rights violations committed by security forces in Papua,” said Joanne Mariner, Director of Amnesty International’s Crisis Response Programme.

“Investigating such cases and holding perpetrators accountable are key to upholding human rights and achieving peace in Papua.”

Restrictions on movement, appearances

Amnesty International’s research has revealed that severe restrictions on the freedom of movement of local residents have accompanied the security build up and escalating conflict. Residents said they had to ask permission from Indonesian security forces to carry out mundane activities such as gardening, shopping, or visiting another village.

Lian said: “When we go to town for shopping, we are asked where we go, which village we are coming from, where we live. Then after shopping, while we are going home, our stuff is checked. Even our bags have to be checked every day by the security apparatus.”

Security forces also restrict the use of electronic devices such as mobile phones and cameras, according to interviewees who also alleged that, on occasion, Indonesian security forces have detained them for their hairstyles, which authorities sweepingly associate with pro-independence fighters.

“Our people like to have long hair; it is part of our culture, not only in Papua, but in Melanesia. I have been asked more than 10 times about my hair and moustache. They arrest many people for having long hair and moustache. They get asked, hit,” Gema, a local resident, said.

Background

Amnesty International takes no position on the political status of any province of Indonesia, including with respect to calls for independence. The organization documents human rights violations whatever the political context in which they are committed.

Note to Editors: *Names have been changed for security reasons.