This month the trains increased their regular schedule to 48 trips per day from 44 after a review of ridership trends, the Jakarta Globe reported. Service started at just 14 trips per day.

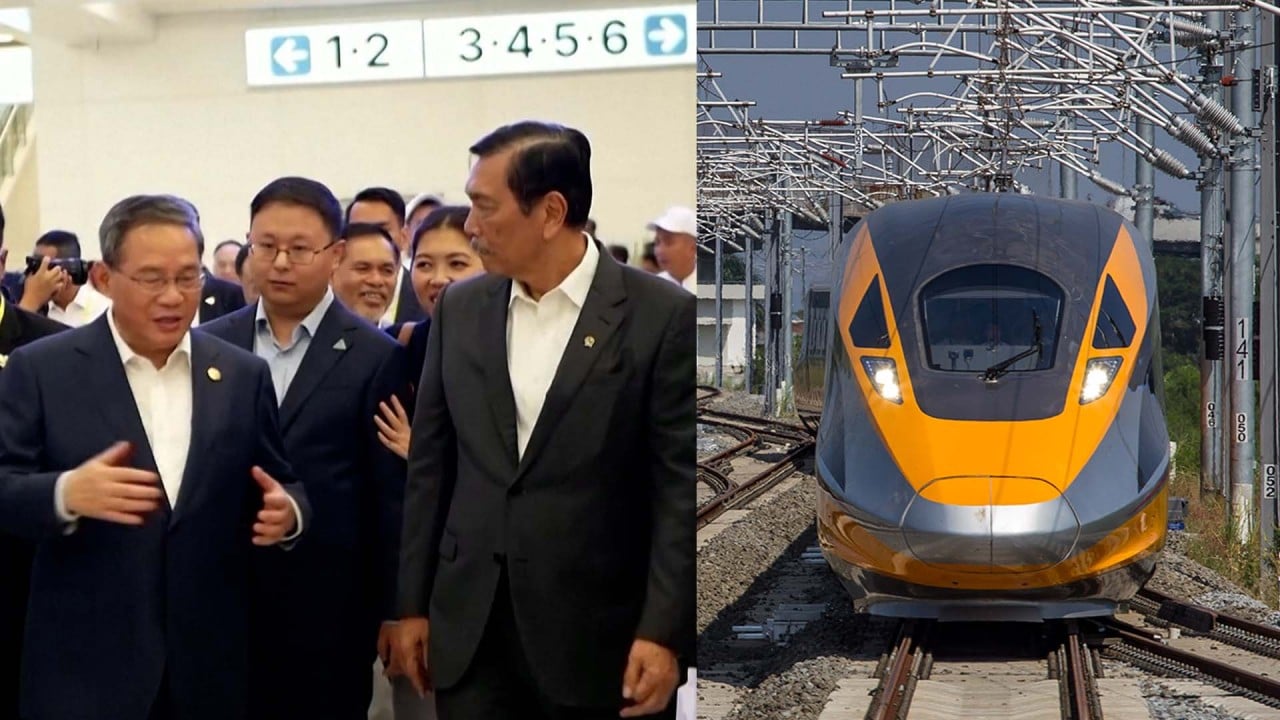

The railway, branded “Whoosh” – its red and silver trains can move as fast as 350kph – is expected to continue attracting travellers who live near the four stations, including one outside the capital Jakarta and one near Bandung, a tourist city 158km (98 miles) to the southeast.

But ridership over the past six months cannot predict whether the railway’s popularity will be sustainable and wide-ranging enough to turn profits, analysts said.

“There is a possibility that passengers lose their excitement, that they stop using this train and go back to their old style of commuting,” said Siwage Dharma Negara, a senior fellow with the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

So noteworthy was the railway that Indonesian President Joko Widodo was present for the launch of the US$7.3 billion project in October.

The railway boasts travel times of 40 minutes from beginning to end, versus three to four hours by normal train or road. Fares between 150,000 Indonesian rupiah and 600,000 Indonesian rupiah (US$9.4 to US$38) are seen as affordable for the middle class, and riders say prices sometimes drop during less popular seasons. Fares for slower trains can cost as little as 80,000 rupiah.

As road congestion grows in Jakarta and Bandung, high-speed rail could become all the more attractive, Negara said. Jakarta has more than 11 million people, and Bandung 2.7 million.

The project took seven years to build, following a pandemic-induced delay and a US$1.2 billion budget overrun.

It made everything easy for us … The station was clean, the staff was helpful and the train was right on time

Bandung has more pull now as a getaway for people in Jakarta, said Nukila Evanty, a member of the Asia Centre research institute’s advisory board. High-speed rail appeals to those “who want to appreciate the time”, the Jakarta denizen said.

“It made everything easy for us,” said Shreemanjari Tamrakar, a 37-year-old Nepalese tourist who rode the railway in April. “The tickets could be bought online. The station was clean and systematic, the staff was really helpful and the train was right on time.”

The railway has already lifted public opinion of Chinese technology, observers said.

“Among Indonesians, we have certain negative perceptions about Chinese technology, like it’s definitely cheap but easily broken,” said Muhammad Habib Abiyan Dzakwan, a researcher in the Department of International Relations with the think tank CSIS Indonesia. “But now China can compete with Japan.”

However, total travel time can be more complicated than the marquee figures suggest. The stations closest to Jakarta and Bandung are in suburbs, requiring passengers to take feeder trains, buses or minivans from the inner city – and the latter two options would face notoriously heavy traffic when leaving urban Jakarta.

Another possible weakness: Many travellers, including some who live in Bandung but spend weekdays in Jakarta for work, have become accustomed to minivans and slow trains, both of which charge more affordable fares for Indonesia’s numerous low-income travellers.

“We already have enough transit from Jakarta to Bandung,” said Roseno Aji Affandi, an international relations lecturer at Bina Nusantara University in Jakarta.

Affandi has taken high-speed rail several times, and estimates from personal experience that ridership reaches just 20 per cent capacity on some days. “It was busy in the beginning, but today we may see that it’s not feasible for economics,” he said.

Affandi describes his Whoosh trips, mostly for business, as “satisfactory”, with quality “adequate and stable”. But scheduling and pricing, he said, make slower trains or shuttle buses – which stop near his home and workplaces – “a better option for my needs”.

The Jakarta Post says the debt will reach 3.15 trillion rupiah (US$197.7 million) in year one, even after earning nearly 2 trillion rupiah from ticket sales.

Mounting debt, Negara said, would burden the state-owned investors backing the project, particularly the Indonesian national railway firm Kereta Api Indonesia.

China lent money covering 75 per cent of the project’s construction, with a 40-year term and a 10-year grace period. Bank loans may be needed to clear a further debt of 3.15 trillion rupiah, Negara said.

Some Indonesians already feel “concern” about the scale of the amount owed, Dzakwan said.

In October, Indonesian media outlets quoted the PT Kereta Cepat Indonesia-China president director as saying Whoosh would take less than 40 years to turn a profit.

The company did not answer multiple requests for comment.

To attract passengers, the operator will probably use marketing and arrange more feeder transport at both ends of the line, analysts said, with some Jakarta denizens predicting property developers will build housing around the suburban stations so passengers can live nearby.

Reliance on suburban railway stations anywhere in the world “can be a forward-looking way to anticipate the needs of ever-expanding urbanisation”, said Dan Prud’homme, an assistant professor at Florida International University’s College of Business.

The operator will attract passengers by running trains on time, keeping the railway safe and “marketing” so people know about it, Negara said.

Paramitanigrum, an international relations lecturer at Bina Nusantara University, does not ride Whoosh despite living in Jakarta. Minivans to Bandung “stop all over town”, she said. But she would take the high-speed rail to Surabaya in the event of an expansion. “That would really save time.”

Even with numerous obstacles, China is in all likelihood pleased with the project so far.

Indonesia’s enthusiasm for the rail line – expressed via capital outlays, efforts to popularise the train and vision for its expansion – have not been replicated in many countries, said Zha Daojiong, an international studies professor at Peking University.

I don’t see the rail in Indonesia as a model for other societies … Many are just not yet ready

“I don’t see the rail in Indonesia as a model for other societies,” Zha said. “Many other societies are just not yet ready.”

Similar high-speed rail systems, such as those in Japan and Taiwan, have struggled with debt but maintained operations – sometimes with government subsidies to keep prices affordable.

China outbid Japan in 2015 to build the Indonesian railway.

“The rail project in Indonesia is projected as a success in terms of both Chinese industrial capacity and its capacity to prevail in international competition,” Prud’homme said.